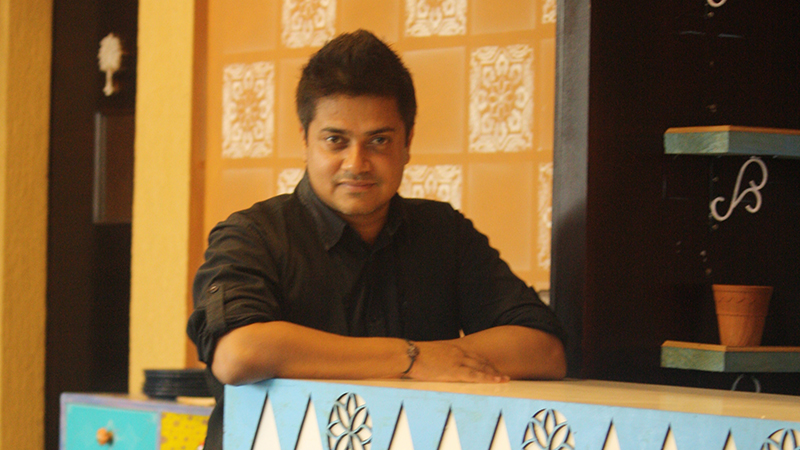

He has manned the pass of some of the country’s most loved kitchens; he has cooked for luminaries, Bachchans, Ambanis, F1 teams, you name it; he has a portfolio of restaurants under his apron; he has bagged multiple Chef of the Year awards; appeared on TV shows, and mentored many a budding chefs. Say hello to Sabyasachi Gorai, lovingly called Chef Saby, who introduces himself as ‘Ami Shob-o-Sachi’ (I am Sabyasachi, in Bengali). Clocking in almost 100 hours a week, the gent who made the gamcha sassy is nowhere near hanging his chef’s whites. Having checked most to-dos on any chef’s list, he’s craving more at 46. “It is the creative expression that keeps me going alongwith a yearning to leave a legacy. I feel your name should connect with something that you do. Be it the pictures you click, the paintings you make, the designs you envisage, and in my case the food that I cook. I’d like to leave footprints.”

Chef Saby may have introduced tasting menus way back in 2003, but the man enjoys eating out of bowls. He will lap up a bowlful of soup, ramen, noodle bowls, khichdi, biryani, or rajma chawal over an elaborate thali any day. Flat surfaced plates featuring a multitude of dishes don’t whet his appetite. “I am very happy cooking, and eating one-pot meals. I like to cook biryani in large handis, risotto and porridge in big pots, and paella in giant pans. I feel connected to meals like these,” shares the chef whose cooking utensil of choice is a dutch oven. “I am fascinated with cooking on wood fire. A tripod over which a traditional black cast iron pot is hung low is ideal for me. These meals bind people together,” says Chef Saby, the feeder who loves hosting feasts.

Image: etsy.com; Traditional one-pot meals

Given his pick of cooking methods and averseness to multitude, it isn’t surprising that Chef Saby’s restaurants mirror his unconventional trait, “I dare to walk away from the beaten path. We will never have DJ nights or ladies’ Tuesdays in our restaurants. We’re not very commercial in nature. Commercial success of my restaurants is a byproduct of good work.”

An Arts graduate from Calcutta University, Chef Saby enrolled himself into IHM, Calcutta, and topped the third year in cookery, a feat that failed to impress his father, a literature loving Bengali. The path was chosen, nevertheless. The ex-Director of Kitchens at Olive Bar & Kitchen almost never wanted to open a restaurant of his own for he couldn’t think of what to cook there. He moved to being his own boss in 2012, and donned the Ring Master robes at Fabrica by Saby, a boutique restaurant consultancy. Whilst Fabrica was slowly gaining momentum, a chance flip of the pages of his father’s (Sakti Gorai) book, 100 years of Coal Mining History, seeded the idea of his first restaurant Lavaash by Saby. In the book he stumbled upon old pictures of graves that jogged his memory back to his hometown Asansol, West Bengal, and its Armenian settlers of the late 18th century.

Image: Lavaash Bar & Lounge; Lavaash by Saby

“My childhood treats had goodies from Armenian-run bakeries every Christmas. It was, in a way, my family legacy too. My father had preserved Armenian recipes as cuttings and in diaries. My grandmother’s 1930s cookbook had some gems too,” he shares. “But with the Armenian settlers long gone, their food was not being cooked but their cooking methods are still widely used,” he tells. “Baking is a gift from the Armenians. They gave India the tonir (tandoor), the Lavash bread (recognised by UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage), and tolmas. They even introduced West Bengal to cheese and curd. Stews, dumplings, stuffed pointed gourd (parval) were cooked by them. I resurrected these at Lavaash by Saby where we serve Armenian cuisine with Bengali touches,” he talks about his restaurant that overlooks the majestic Qutub Minar. Housed in the quaint Ambawatta Complex, its interiors are redolent of Mediterranean and Armenian homes, with hues of blue, complete with peacock motifs that adorn windows to upholstery.

Besides deeply-researched concept restaurants, the culinary entrepreneur’s approach to recipes is noteworthy. Being dyslexic, this chef uses this to his advantage in the kitchen, “My recipes come from memory flashes. I had eaten Catalan stew at someone’s home in Catalonia. If you tell me to make it, I will make it with my eyes closed. The final product could be reddish, but no recipe book can tell you which shade of red – vermillion red, brick red, blood red or burnt amber red. My brain copies that. So my dyslexia is advantageous in the kitchen to recreate dishes or experiences from my travels.”

Upon being prodded to reveal the method behind his madness, the storyteller lets us in on the works, “Concepts arise from flashpoints in my brain, memory sparks or déjà vu. It could be a childhood memory or a travel moment that makes culinary sense.” He has a Pan Asian concept tossing and wok-ing in his head, “The concept is different from run-of the mill Pan Asian restaurants. It is the story of erstwhile India woven into a Pan-Asian concept. My father’s home town, Tamluk, the ancient Tamralipta, was the starting point of the Mauryan trade route. The place was also roughly where the Silk Route was born. Tamluk led Mauryans to South-East Asian countries. There exist beautiful stories about Buddhism (which flourished in Tamluk) exiting from here to other South-East Asian countries.” The chef dismisses the mention of regional food as a trend, saying, “Indian restaurants are always confused. They always had weird dishes like Dal Makhni and Butter Chicken which are nothing but hit commercial concoctions nowhere to be found in Punjabi households. The diverse Indian communities eat and serve their food differently. All of it is mainstream food, and that is how Indian food should be showcased. It is no trend. Every community will eventually come forth and talk about their food. That is what the Parsis, Sindhis, Bihari and Bengalis are doing – taking pride in their cuisine which connects them to their roots.”

Left: Armenian style dumplings at Lavaash by Saby

“Mine was not a fairytale childhood,” he says. “Spending afternoons in the nearby crematorium and playing in the evening on koyele ka dher (coal dumps) cannot be ideal,” he shrugs. “My father’s government job fetched us a lower middle class upbringing,” says the chef who grew up in dry and arid Asansol, a miner’s town.

No prizes for guessing that Mineority by Saby, his restaurant in Pune, is based upon stories from Asansol. “Mining communities around the world are quite a spirited lot,” he explains. “Mining clubs have been around for the longest time, especially in mining towns. When miners resurface, they rejoice. In India they might enjoy desi daru or chullu, and elsewhere they would hit pubs as they are never sure if they’d be part of the merrymaking the next night. The city of Ballarat, that witnessed the Victorian gold rush, is a great example of the spirit of miners,” he says.

Chef Saby places a great sense of pride to the region he traces his roots to. Soaked in nostalgic memories of Burnpur Bakery and Abdul Wahid bakery of Asansol, Chef Saby reminisces, “As children, we used to love cakes wrapped in butter paper, or those decadent cream horns.I inducted these memories on the Mineority menu as Childhood on a plate wherein the cream horn and a glass cake come with chai cream.” Another such memory birthed the Jurassic cheesecake at Mineority made from Chenna Poda, a cheese based dessert that he ate during his days in Bhubaneswar. Travelling for food is a hobby for Chef Saby who observes, “In Thailand, the tradition of food from push carts is very much alive. You get amazing pastries rolled out from a cart. We, in India, try to be fancy. The era of freshly baked biscuits carted out from local bakeries, home delivered on a bicycle twice a day, is no more.” So the chef took two cookies from the hinterland of India, thekua, the Bihari biscuit, and gauja from Orissa, and turned them into Dehati cookies and cream on the Mineority menu.

He appreciates all things natural and all things local,“I am obsessed with using single origin oils like olive, sesame and mustard. They are a medium that carry forward the flavour of a dish. I am fond of whole spices, red chillies to star anise, whole cinnamon to radhuni, mustard to saunf, and even Panch Phoron, the Bengali five spice mix, which I use a lot in Eastern cooking.” Averse to refined white ingredients like iodised free flow salt or white sugar, he shares, “I collect and use naturally occurring salts like sea salt, rock salt, and those from the shores of Gujarat and Orissa. I tilt in favour of sweeteners like shakkar and cane sugar.”

The chef who is influenced by East Indian styles of cooking and takes to Instagram at times to chronicle his food journey, feels, “Social Media allows everybody to upload pictures of what they eat, whether they are aesthetically shot or not. Many restaurants use the medium well to their commercial advantage. I am told restaurants should plate Instagrammable food. If you can promote your food business without spending much money on traditional forms of marketing and sales, I see no problem. However, I do believe food should be soulful. It is quite possible that food that looks good in these pictures tastes great too.”

Even as he jets off to Bengaluru to lend final touches to the new flagship 1700 seater restaurant of Big Brewsky, the microbrewery, at Hennur Road, we fire the signature Rapid Fire shots at him.

One day you’d like to cook for?

My daughter.

Your favourite dining companion?

My daughter with whom I hit KFC.

Your best kitchen moment?

The pop up at the Norwegian Vice Chancellor’s house in Bandra (Mumbai) where the BBQ didn’t fire and the pots and pans didn’t arrive. We had a two-burner gas and a small oven for equipment. Despite all odds, the food was much appreciated.

List three books that you keep going back to.

The Kitchen Session by Charlie Trotter, Tetsuya by Tetsuya Wakuda (for his philosophy of ‘less is more’), and Rockpool Bar & Grill by Neil Perry.

Name three chefs who inspire you.

Charlie Trotter, Tetsuya Wakuda and Neil Perry.

One advice you’d always give younger chefs?

Work hard to grab the opportunity to success.

This conversation is a part of the DSSC Secret Conversation Series, where we get candid with the ace industry disruptors who map its course one masterstroke at a time.